By Mao Keji

India has been one of the fastest-growing large economies in the world for over two decades. However, the country's performance in terms of GDP growth and macroeconomic stability has been dwarfed by that of China.

This disparity can be best illustrated by the two countries' respective economic trajectories: Although they had similar economic status in the 1990s, China's economy has grown much faster since then and is now almost five times bigger than India's.

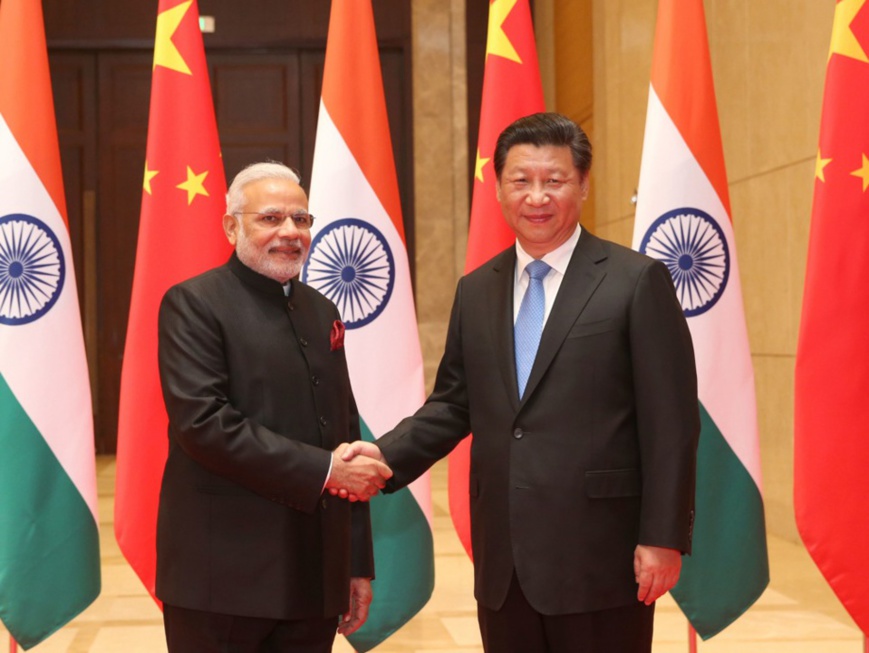

Given this situation, closer Sino-Indian cooperation may be the right solution for some of India's economic problems. To this end, instead of viewing India and China as being on an equal footing as the representatives of emerging markets, we should recognize both China's head-start and India's unrealized potential for growth. This would be more conducive for assessing the promising future of Sino-Indian economic cooperation.

As countries that both have populations of over 1 billion people, China and India share three important advantages: a large and low-cost labor force; a large domestic market; and a great supply of high-quality human capital known for professional services and science and engineering talent.

Utilizing these three assets, China followed a three-step model. First, it focused on labor-intensive and export-oriented industries like clothes, toys and furniture at the low end by tapping into its huge workforce.

Then, with initial capital and expertise accumulated, it exploited growing domestic demand on the one hand by initiating policies that encouraged more transfer of technologies from developed countries, and on the other hand by taking advantage of its own economies of scale to develop national champions.

China then turned its attention to research and development, utilizing its large reservoir of talent. In this way, China expects to reap high value from cutting-edge industries like integrated circuits, pharmaceuticals and aviation.

Interestingly, though it has the same three advantages, India's approach followed a reverse sequence: For decades, India has been famous for its highly competitive technology- and capital-intensive industries like pharmaceuticals and IT services. While India's intermediate-tier industries, such as cellphones and automobile parts, have made major progress in recent years, they still lag behind in terms of international competitiveness and the industrial ecosystem.

Ironically, and deviating from the conventional growth pattern, India's labor-intensive manufacturing sector is disproportionately underdeveloped, leaving its huge workforce largely in less productive informal sectors.

Such a distorted industrial development pattern has taken a heavy toll on the Indian economy, which has been unable to meet the massive domestic demand for manufactured products, forcing Indian consumers to rely on imported goods. The country has also failed to provide enough employment opportunities for its ever-swelling ranks of job-seekers.

Many of the major fragilities and risks currently facing the Indian economy - such as overreliance on foreign capital inflows, fragile foreign exchange rates, vulnerability to oil price hikes, insufficient formal job creation, and susceptibility to fickle monsoons - are largely a result of its underdeveloped and uncompetitive industrial sector. This could be relieved by realizing India's huge industrialization potential.

Although Indian decision-makers have highlighted industrialization, especially since Narendra Modi's election as prime minister in 2014 and through the "Make in India" initiative, perhaps New Delhi was never so consciously pressurized to accelerate the development of its manufacturing sector as it is today. Linking directly to political outcomes, these challenges loom even larger for the Modi administration as the 2019 general election is fast approaching. After all, India's dire job market and the recent poor performance of the rupee may all remind Modi that the long-term solution lies in industrialization.

At this point, it is important to consider what role China could play to further India's industrialization. As the only country in the region, with a similar population size and development trajectory, China's growth history can not only provide important lessons and experience; the country could also offer critical material assistance in the form of direct investment and capacity transfer. If China and India continue to improve their mutual trust and deepen cooperation in industrialization, they may achieve something far beyond their expectations.

It would be best for Sino-Indian cooperation, for the time being, to be focused on labor-intensive and export-oriented industries, which could tap into India's abundant labor resources. Considering both countries' comparative advantages, such cooperation may well relieve India's current trade deficit, and other issues such as overreliance on foreign capital and insufficient employment opportunities, while providing China with more avenues for growth. Industrialization is vital for India to become a global economic powerhouse, and China can benefit by playing an active role in this. Fortunately, both India and China now seem readier than ever to deepen bilateral cooperation in this aspect.

The author is a researcher with the Pangoal Institution.

Source: People’s Daily/Global Times

This disparity can be best illustrated by the two countries' respective economic trajectories: Although they had similar economic status in the 1990s, China's economy has grown much faster since then and is now almost five times bigger than India's.

Given this situation, closer Sino-Indian cooperation may be the right solution for some of India's economic problems. To this end, instead of viewing India and China as being on an equal footing as the representatives of emerging markets, we should recognize both China's head-start and India's unrealized potential for growth. This would be more conducive for assessing the promising future of Sino-Indian economic cooperation.

As countries that both have populations of over 1 billion people, China and India share three important advantages: a large and low-cost labor force; a large domestic market; and a great supply of high-quality human capital known for professional services and science and engineering talent.

Utilizing these three assets, China followed a three-step model. First, it focused on labor-intensive and export-oriented industries like clothes, toys and furniture at the low end by tapping into its huge workforce.

Then, with initial capital and expertise accumulated, it exploited growing domestic demand on the one hand by initiating policies that encouraged more transfer of technologies from developed countries, and on the other hand by taking advantage of its own economies of scale to develop national champions.

China then turned its attention to research and development, utilizing its large reservoir of talent. In this way, China expects to reap high value from cutting-edge industries like integrated circuits, pharmaceuticals and aviation.

Interestingly, though it has the same three advantages, India's approach followed a reverse sequence: For decades, India has been famous for its highly competitive technology- and capital-intensive industries like pharmaceuticals and IT services. While India's intermediate-tier industries, such as cellphones and automobile parts, have made major progress in recent years, they still lag behind in terms of international competitiveness and the industrial ecosystem.

Ironically, and deviating from the conventional growth pattern, India's labor-intensive manufacturing sector is disproportionately underdeveloped, leaving its huge workforce largely in less productive informal sectors.

Such a distorted industrial development pattern has taken a heavy toll on the Indian economy, which has been unable to meet the massive domestic demand for manufactured products, forcing Indian consumers to rely on imported goods. The country has also failed to provide enough employment opportunities for its ever-swelling ranks of job-seekers.

Many of the major fragilities and risks currently facing the Indian economy - such as overreliance on foreign capital inflows, fragile foreign exchange rates, vulnerability to oil price hikes, insufficient formal job creation, and susceptibility to fickle monsoons - are largely a result of its underdeveloped and uncompetitive industrial sector. This could be relieved by realizing India's huge industrialization potential.

Although Indian decision-makers have highlighted industrialization, especially since Narendra Modi's election as prime minister in 2014 and through the "Make in India" initiative, perhaps New Delhi was never so consciously pressurized to accelerate the development of its manufacturing sector as it is today. Linking directly to political outcomes, these challenges loom even larger for the Modi administration as the 2019 general election is fast approaching. After all, India's dire job market and the recent poor performance of the rupee may all remind Modi that the long-term solution lies in industrialization.

At this point, it is important to consider what role China could play to further India's industrialization. As the only country in the region, with a similar population size and development trajectory, China's growth history can not only provide important lessons and experience; the country could also offer critical material assistance in the form of direct investment and capacity transfer. If China and India continue to improve their mutual trust and deepen cooperation in industrialization, they may achieve something far beyond their expectations.

It would be best for Sino-Indian cooperation, for the time being, to be focused on labor-intensive and export-oriented industries, which could tap into India's abundant labor resources. Considering both countries' comparative advantages, such cooperation may well relieve India's current trade deficit, and other issues such as overreliance on foreign capital and insufficient employment opportunities, while providing China with more avenues for growth. Industrialization is vital for India to become a global economic powerhouse, and China can benefit by playing an active role in this. Fortunately, both India and China now seem readier than ever to deepen bilateral cooperation in this aspect.

The author is a researcher with the Pangoal Institution.

Source: People’s Daily/Global Times

Menu

Menu

China, India ready to deepen their economic ties

China, India ready to deepen their economic ties